Maxwellian Electro-Dognamics

If you care about physics or the history of physics or even just appreciate functioning electronics, James Clerk Maxwell is a big deal. However, as I’ve already mentioned this isn’t the place for going into what exactly makes him and his ideas/discoveries/theories/socially constructed math magic so important (there’s always Wikipedia). This little internet alcove is supposed to be is an outlet for those bizarre stories you collect as you do research, a place to deposit the ephemera of the history of science before all that hard-earned “knowledge” drifts back into the ether.

That said, let’s get back to Maxwell, but not Maxwell the scientist, but instead Maxwell the guy who liked dogs (and occasionally did science with them). After three years of reading stuff by and about Maxwell, I’m now overloaded with dog stories, so allow me to offload them onto you and maybe we’ll get some insight along the way (but probably not).

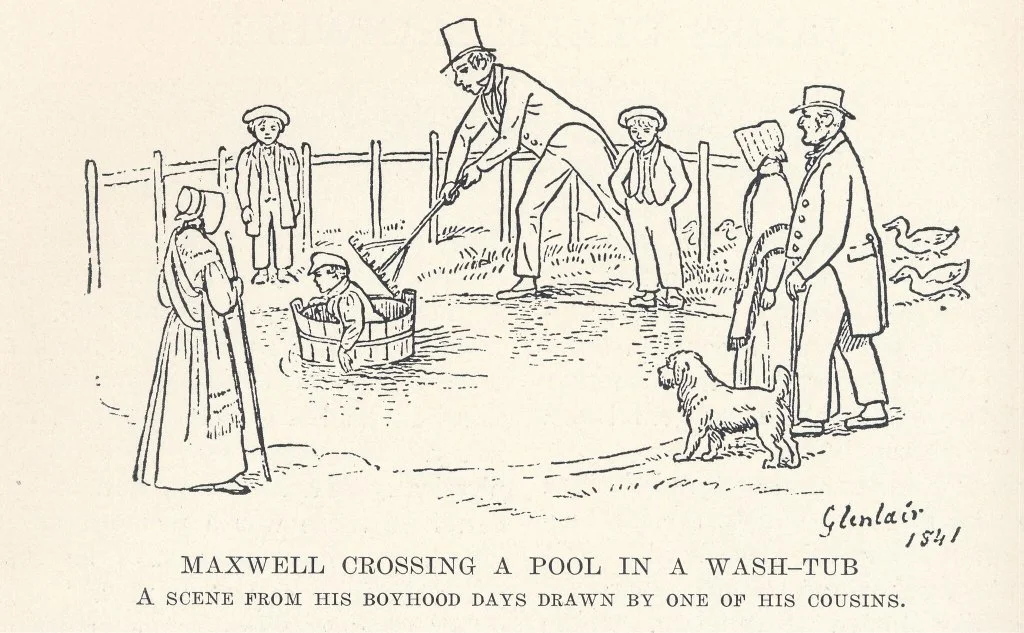

Kid Maxwell grew up on his family’s country estate Glenlair, with a doting father and a kind but short-lived mother. In addition to the small family, there were of course the servants who kept the estate running, cousins who would drop in for extended visits, and as you might have guessed, a number of dogs. The dogs came along for all the typical activities that entertain young boys who have expansive country estates: like sailing across puddles in washtubs

posing for the drawing portion of cryptic mirror-coded letters,

and of course performing awe-inspiring acrobatic tricks

For lack of better hobbies, these stunts persisted into his teens. When Maxwell and his friend/biographer Lewis Campbell stopped by Glenlair during a break from school in Edinburgh, the mustard-colored terrier Toby was still performing twice daily for homemade dog biscuits.

But it wasn’t all just sickeningly wholesome fun and games, Maxwell’s scientific interests rubbed off on his dogs, leading to second careers as both his scientific colleagues and apparatuses. While Coonie (who shared his nickname with Maxwell’s cousin, Colin Mackenzie) did occasionally drop by the Cavendish Laboratory, it was Toby who enjoyed stable employment there. Tobin, Tobs, or Tobit (all at one time or another acceptable Toby nicknames) was unsurprisingly no great fan of the sounds of sparks, a fixture of the Cavendish soundscape circa 1874, but shockingly remained compliant enough to come sit for experiments when called.

This relative complacency kept Toby on the cutting edge of electrical physics. After a vigorous rubbing with a cat’s skin, a properly insulated Tobit was shown to be positively charged. This was quite the scientific coup, particularly from the canine perspective, helping to disprove the supposedly common wisdom that any object rubbed with a cat’s skin becomes negatively charged. Maxwell, quite pleased to have elevated the relative station of dogs as electrical objects, exclaimed “a live dog is better than a dead lion.” No one questioned whether this statement was a weird way to verbalize what they had just witnessed because well-to-do Victorians were just naturally prone to bouts of poetic grandeur. Campbell for his part made a joke about trying it out with a live cat and dog.

So as this episode with the cat’s skin passed without anyone getting mauled, Maxwell continued to misconstrue the intention behind “bring your dog to work” days at the Cavendish. This led to regular sessions involving Toby and an electrophorus (basically a simple, manually operated electrostatic generator), which he mostly put up with.

Again Campbell reassures us that Toby was fine with all of this, claiming that the dog was growling merely “to relieve his mind.” Nevertheless, a modern, less-charitable reader might doubt Campbell’s abilities a dog whisperer and take his explanation to be a bit contrived.

But before the Cavendish and before developing this fetish for testing exactly how loyal his dogs were, indeed before he had done much work of significance, Maxwell spent a lot of time looking at eyeballs. Specifically, he was looking into eyeballs, as the center of a really strange Latourian network that included a few people but mostly a bunch of exceedingly patient dogs. So it was that around 1854, Maxwell built an ophthalmoscope, i.e., a thing to look in through pupils, and started recruiting dogs that would let him (platonically) stare into their eyes.

Why use dogs and not just people, other than to avoid the discomforting intimacy inherent in staring into a stranger’s eyes for minutes at a time? Dog retinas are just better looking than people’s. No matter how visually arresting you might believe your retina to be, you, as a person, don’t have a sort of iridescent reflective tissue behind your retina (tapetum lucidum) and that just makes retinas look far more interesting (human retina on the left, dog retina on the right).

Maxwell thought seriously about his dog network. In letters to his family he talks about the patience of friends’ dogs compared to his own and even laments not having tested dogs he only met in passing. Even William Thomson (not yet Lord Kelvin) wasn’t spared Maxwell’s comments on dog eyes. Spice, Maxwell’s Scotch Terrier, even became something of a tourist attraction at Glenlair. Because the Victorian world was short on real hobbies, the promise of looking into Spice’s eyes drew visits from renowned doctors like William Bowman, Surgeon to the Royal London Ophthalmic Hospital (and apparently handy with an ophthalmoscope). And lest you think this was just something to do while visiting with one of the most highly regarded physicists in the world, the Dutch ophthalmologist Dr. Franciscus Cornelis Donders of Utrecht stopped by for a look even while Maxwell was out of town.

When he was around, the number of people with whom Maxwell was talking or the general din around him occasionally exceeded his ability to concentrate. In these instances, the dogs again became useful allies. When his thinking was bothered by distractions, Maxwell would bring Toby near and calm his mind by repeating the dog’s name over and over as he worked to find an answer. Having come across a solution, he would thank Toby1 for his help and return to the work or conversation at hand. As we learned earlier, Toby would do something similar to calm his own anxiety when confronted with the electrophorus (at least according to Campbell). Whether Maxwell took after his dogs or his dogs after him remains open to interpretation.

He certainly treated his dogs like his kids or at least like his students (as a nice bit of symmetry, he also referred to his students as his “pups”). As an example, Coonie was for a time notorious for howling “unmercifully” whenever anyone played the piano. Maxwell finally cured the dog of its musical affliction, and, when pressed on his methods, deadpanned that he had simply taken the dog over to the piano and explained to him how it all worked, seemingly a conscious reference to Maxwell’s own childhood and his incessant cries of “how it doos?” So while it’s unlikely Maxwell actually trained his dogs through lectures on mechanics and acoustics, he nevertheless joked about them in such a way as to reveal his profound connection to them.

So have we learned much about Maxwell the scientist? No, not really, aside from the fact that he was a real human with a real life and a multispecies support network. Have we stumbled into an early draft for some sort of “Dog as Scientific Object in Victorian Britain” anthology? Definitely not, although it's worth noting the stark difference between our modern emotional detachment from the various lab animals that we experiment on and Maxwell's willingness to electrify his beloved pets. Nonetheless, perhaps we can now can better appreciate the lovely statue of Maxwell and Toby that sits in George Street, Edinburgh as more than a ploy to trick children into learning about yet another old dead Scotsman, but rather as conveying something central to his person.