Kepler’s Mysterium Dogmographicum

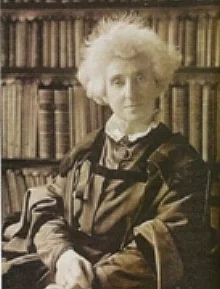

As I was looking through Maxwell’s collected letters (made possible by historian Peter Harman) in search of dog references for the first piece I wrote here, I came across a bittersweet exchange between Maxwell and his friend, the astronomer and astrophysicist William Huggins. Huggins and his wife Margaret Lindsay Huggins were early practitioners of astronomical spectroscopy, i.e., using spectral lines to figure out what stars and other celestial bodies are made of. Adorably, Mr. and Mrs. Huggins met due to their shared interest in spectroscopy.

The first letter, dated May of 1872, is from Maxwell and his dog Toby sending along their photographs (which have not survived) with “our best regards to you and Kepler.” Maxwell is of course not paying his respects to Johannes Kepler, the long dead giant of 16/17th-century astronomy, rather the Kepler he and Toby are acknowledging is Huggins’ much loved English mastiff (the Hugginses also had a terrier, fittingly named Tycho Brahe, although more commonly called Tycho Barky, that lorded over Kepler). It’s this canine Kepler (see picture at the top of the page) that acts as the main character of this narrative, weaving his way through the lives of some of the most prominent scientists of the late 19th century.

In the second letter, dated 1874, Huggins includes a parallel kind of pleasantry, sending his love to Maxwell’s dogs Toby and Coonie, “but especially to Coonie.” Finally, a third letter sent by Maxwell in 1877 attempts to comfort Huggins in the wake of Kepler’s death. Having felt the loss of multiple dogs (and indeed multiple Tobys), Maxwell was most able to, as he said “enter into the feeling of the melancholy home it makes when a dear doggie dies.”

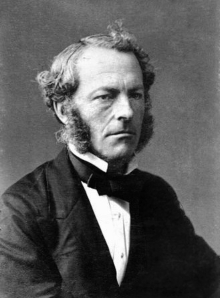

Now we’ve got approximate bookends for Kepler’s life (he was actually born in 1871, close enough) and a first point of connection— to Maxwell, no less. But what did Kepler get up to in those intervening years to warrant me writing all of this? From these letters between Huggins and Maxwell, I was led by Harman’s meticulous references to the Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of the Late Sir George Gabriel Stokes (catchy title) in which Kepler makes his second appearance. Here Kepler appears as a key figure in an amusing recollection of Huggins regarding a dinner he had had with the late Professor Stokes.

For those who may be curious Stokes was a giant of mathematical physics in the second half of the 19th century: Lucasian Professor Mathematics at Cambridge University (Newton’s old chair), a pioneer in the study of all things waves such that he was led to investigate the dynamics of both standard fluids (Navier-Stokes equations) and light, the latter of which resulted in a very strange elastic solid ether (light waves needed something to “wave” and they had to wave it very rapidly), and lastly a longtime secretary of the Royal Society and eventually its president.

Anyway, back to this crucial dinner. After the two men finished eating, Huggins

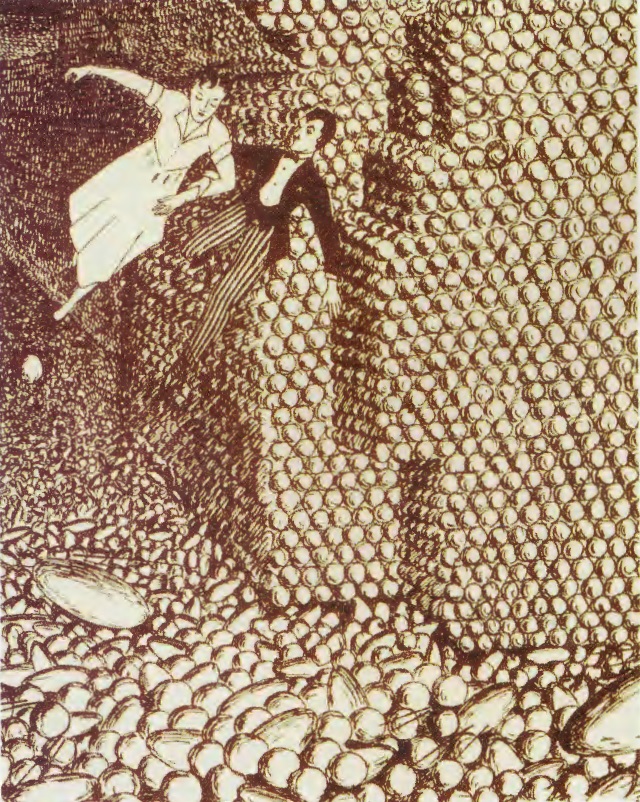

asked him to examine a mastiff which I then possessed, in elementary mathematics. I claimed for my dog, whom I had named Kepler, that he would answer with accuracy any algebraical questions, of which the answers could be given by a number of barks not exceeding five or six.

Stokes took the bait and after completing a successful round of mathematical testing with Huggins’ dog (even square roots weren’t off limits), he seemed convinced that Kepler was actually solving math problems, or as he put it, that “there was clearly mind of some kind at work.”

Both of the Hugginses’ assessments of their dog’s mathematical aptitude were more subdued. Both suggest that Mr. Huggins was probably the only one doing any arithmetic, while Kepler merely read William’s face to figure out when he had barked the right answer. This extreme perceptiveness on Kepler’s part was apparently entirely within character. He was also known for his ability to differentiate various guests as they approached his home, alerting his owners of the relative familiarity of the guests with a different bark to indicate whether they were a close friend, acquaintance, stranger, or enemy.

Nevertheless, Mr. Huggins’ uncertainty regarding Kepler’s methods is still pretty odd (he even claims to have “endeavoured to avoid giving him any sign”), given that we must assume it was Huggins who had initially trained the dog in mathematics. Even if the how behind this trick remains a bit mysterious, the why of it is not; Kepler was paid handsomely for his “calculating” in generous slices of cake (one assumes not chocolate cake).

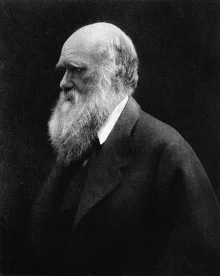

So having earned the affection of the notoriously reclusive Maxwell, and impressed the mathematical genius Stokes, Kepler took a break from physicists to make inroads into biological theory. The circumstances of another of Kepler’s behavioral curiosities were so peculiar that they inspired a communication to the journal Nature entitled “Inherited Instinct,” written by none other than dog aficionado and the father of modern evolutionary theory, Charles Darwin.

Darwin’s letter serves as an introduction to William Huggins’ accompanying letter and contains a general discussion of the heritability of behavior. In his short letter to the journal, Darwin suggests that instinctual behaviors may arise out of “habit and the experience of their utility” (like the fear of people which he claims to have instilled in some otherwise oblivious island birds) while others may just appear somewhat randomly. Ultimately, however, these behaviors can supposedly be passed down to offspring and live on through a lineage of animals. These inherited instincts may or may not be acted upon by selection, be it natural selection, or as in Darwin’s stated example of the tumbler-pigeon, artificial. Darwin insists that the accompanying letter from Huggins affords an excellent and unique example of inherited instinct; it does not disappoint.

As it turns out, Kepler doesn’t like butcher shops. Even at six weeks old, Huggins tells us, passing by the first butcher shop he had ever seen, Kepler was not happy. At six months old a servant was so completely unable to convince him to pass by a butcher shop that despite their insistence (English mastiffs get pretty big) they ended up having to take an alternate route home. In the years since that episode, Huggins had made some effort to train out a little of Kepler’s fear of butchers (Kreopolisophobia) and Kepler would now allow himself to get slightly closer when passing a butcher shop.

If you've been paying attention, you might have already gathered from Darwin’s lead-in that Kepler probably wasn’t the only one in his family with this affliction. Indeed, Kepler’s father Turk, Kepler’s grandfather King, as well as his two half-brothers (all of different mothers) Punch and Paris were all terrified to varying degrees of all things related to butchery. For his part, Paris made Kepler’s fear seem trivial by comparison. When a master-butcher, out of uniform, attempted to pay Paris a visit at his home, the dog became so agitated that he had to be locked away in a shed and the meeting was aborted. And yet this was hardly Paris’ most serious anti-butcher outburst:

The same dog [Paris] at Hastings made a spring at a gentleman who came into the hotel. The owner caught the dog and apologized, and said he never knew him to do so before, except when a butcher came to his house. The gentleman at once said that was his business.

And so Huggins concludes, the cause of Kepler’s anxiety can’t be found in the dog’s own past, rather his fear of butchers has been inherited (patrilineally apparently). The natural question then is if this all started with King (Kepler’s great-grandfather was untroubled by butchers), what the hell happened to Kepler’s grandfather to start all of this? What kind of horrors did he suffer at that hands of some deranged, dog-hating butcher? Well, as Darwin informs us,

Unfortunately it is not known how the feeling first arose in the grandfather of Dr. Huggins’s dog. We may suspect that it was due to some ill-treatment; but it may have originated without any assignable cause, as with certain animals in the Zoological Gardens, which, as I am assured by Mr. Bartlett, have taken a strong hatred to him and others without any provocation.

Sure Mr. Bartlett, sure. You know what you did.

So without a copy of Margaret Huggins’ privately published biography of Kepler (yes that's a thing and if you happen to have inherited a copy don’t hesitate to shoot me an email), that’s it for this account of Kepler the dog. Loyal companion and doorbell to both Mr. and Mrs. Huggins, friend to Maxwell, obedient (like his namesake) to Tycho, mathematical rival of Stokes, troubled case example of Darwin, and favorite of all the readers of the February 1873 edition of Nature.